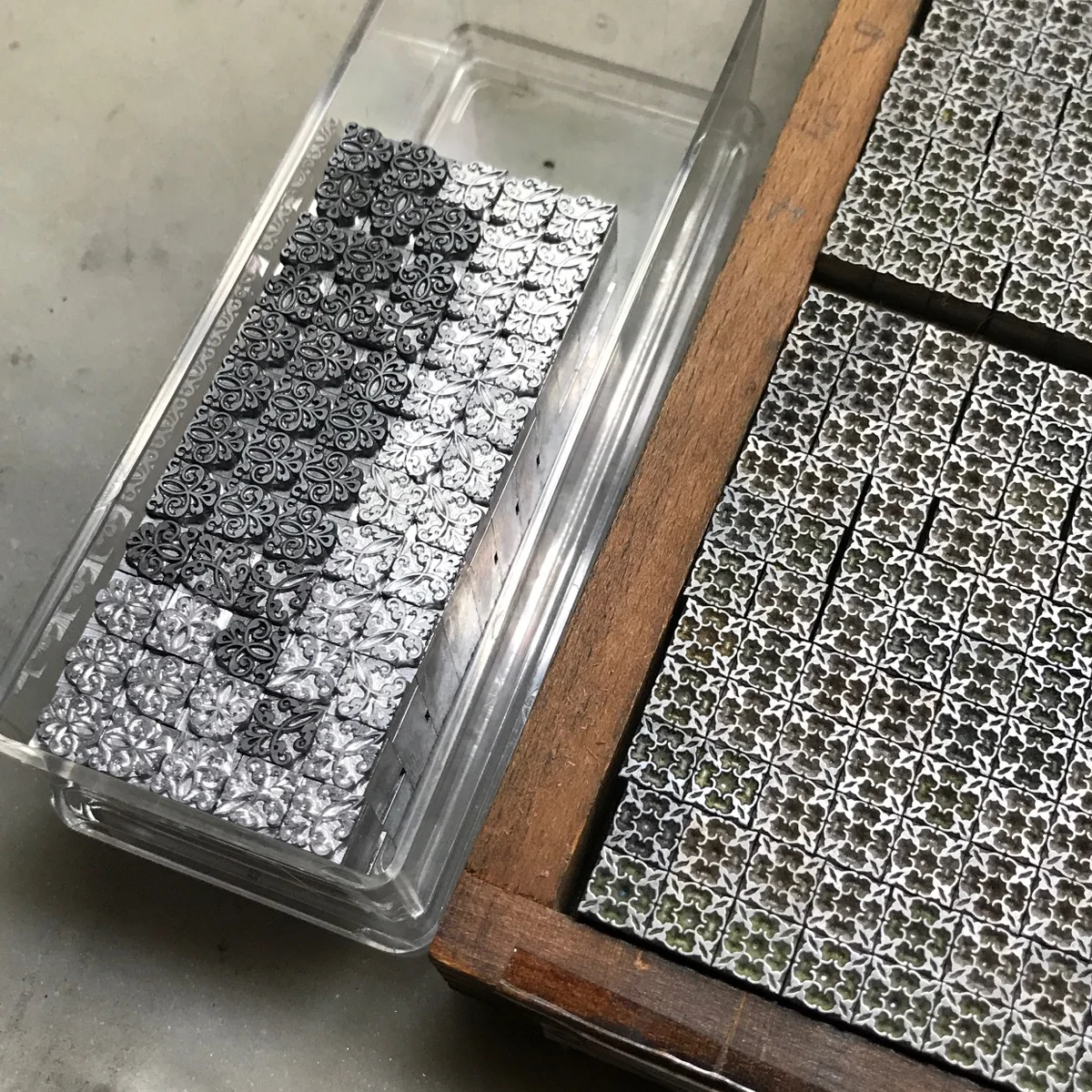

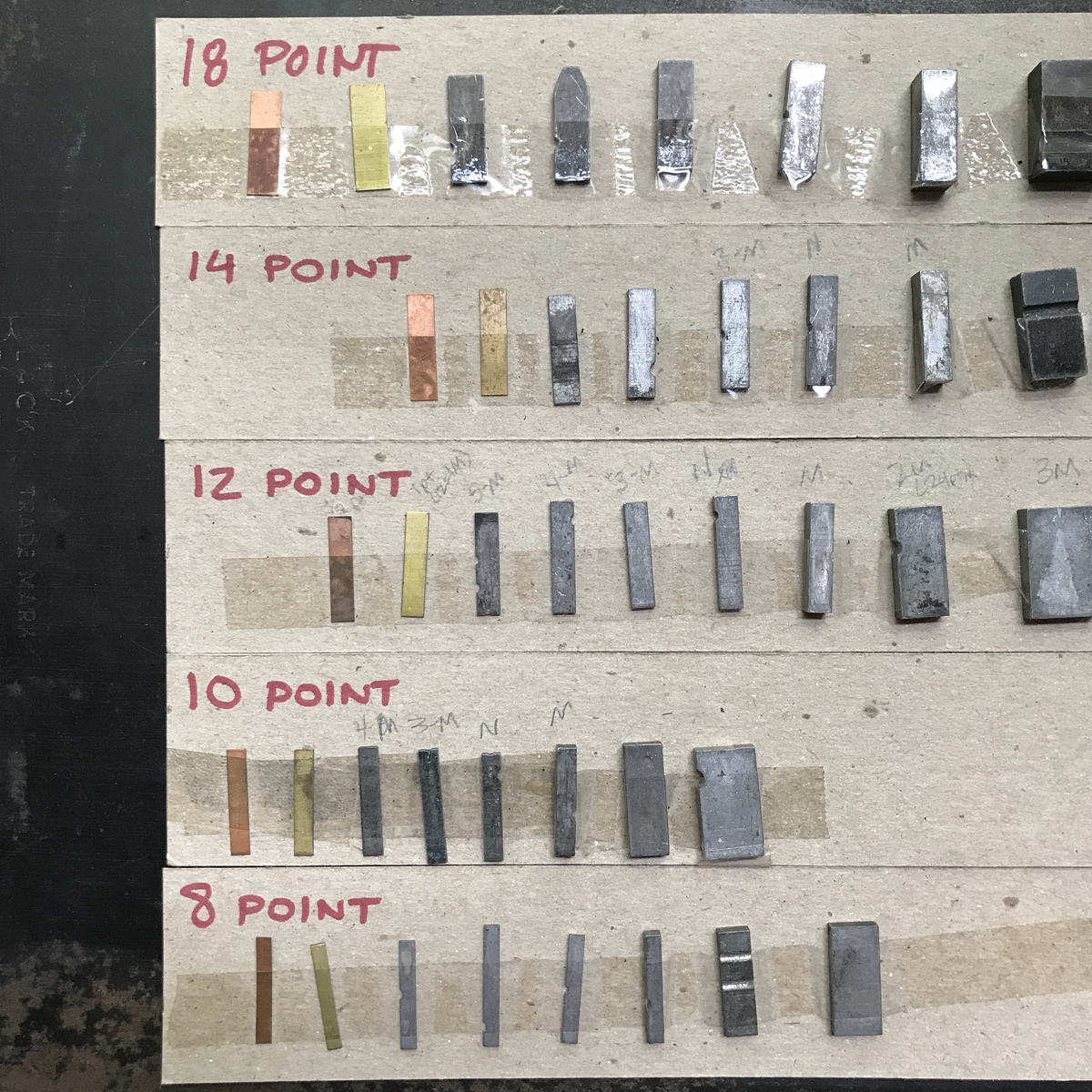

Sometimes the best ornamental experiments come from the simplest pieces in your collection. No doubt you've seen countless small handy boxes at various letterpress events and sales. Sold as auxiliary sorts for your existing type collection, they range from dots, lines, mathematical figures, parenthesis, and foreign accents. Don't pass them up! You can create a range of work with very few pieces and the bonus is they take up so little space.

I pulled out squares, dots, brackets and parenthesis from my collection.

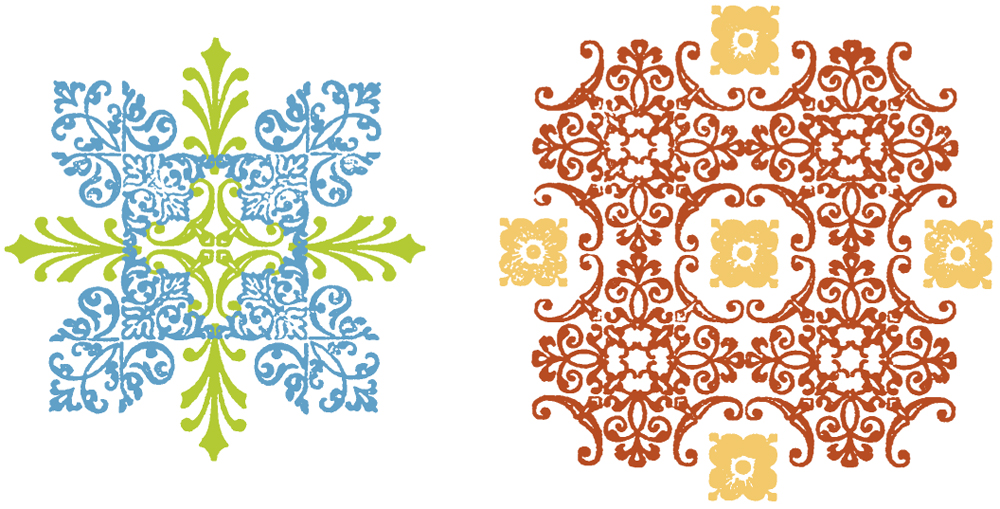

Here are two quick forms set directly in a composing stick, using just sorts from these four boxes. To keep it even simpler, I used only those that broke down to 6, 12, 24 or 36 point.

I put the sticks on press for a quick, down-n-dirty carbon proof to see what the pattern revealed.

So much potential with even the simplest shapes! So when you come across these handy boxes, don't pass them up; just think of the repeating patterns and illustrations waiting to be printed.